I first read Ruth’s article about going overboard when it was first published in the Caribbean Compass back in 1999.

It was an amazing story and I wondered if I could possibly be as resourceful as Ruth if something like that happened to me. Before I went cruising, I thought if anything bad happened out on the sea, well, there is no way I could possibly cope.

Once cruising though I began to learn however, that occasionally the inthinkable does occur (as it does on land as well), and I started meeting people who had coped with all sorts of emergencies and survived.

This knowledge of course doesn’t make you complacent, in my case it made me less panicked and more able to think: what is the best way to avoid a major problem, and how should we respond in an emergency.

We all eagerly await the monthly arrival of the Caribbean Compass in the anchorages down island, and it is a special achievement to have an article published in the Caribbean Compass. Probably nothing gives a truer picture of what Caribbean cruising is like in all its variety than the articles that Sally Erdle, editor and former circumnavigator publishes in the Compass.

Thank you Sally Erdle and Rona Beame for putting together a book of all the best stories from the Compass! I am sure I have missed some of these stories the first time around, and others like Ruth’s, I was glad to have the chance to reread again and be amazed.

— Kathy Parsons, Women and Cruising

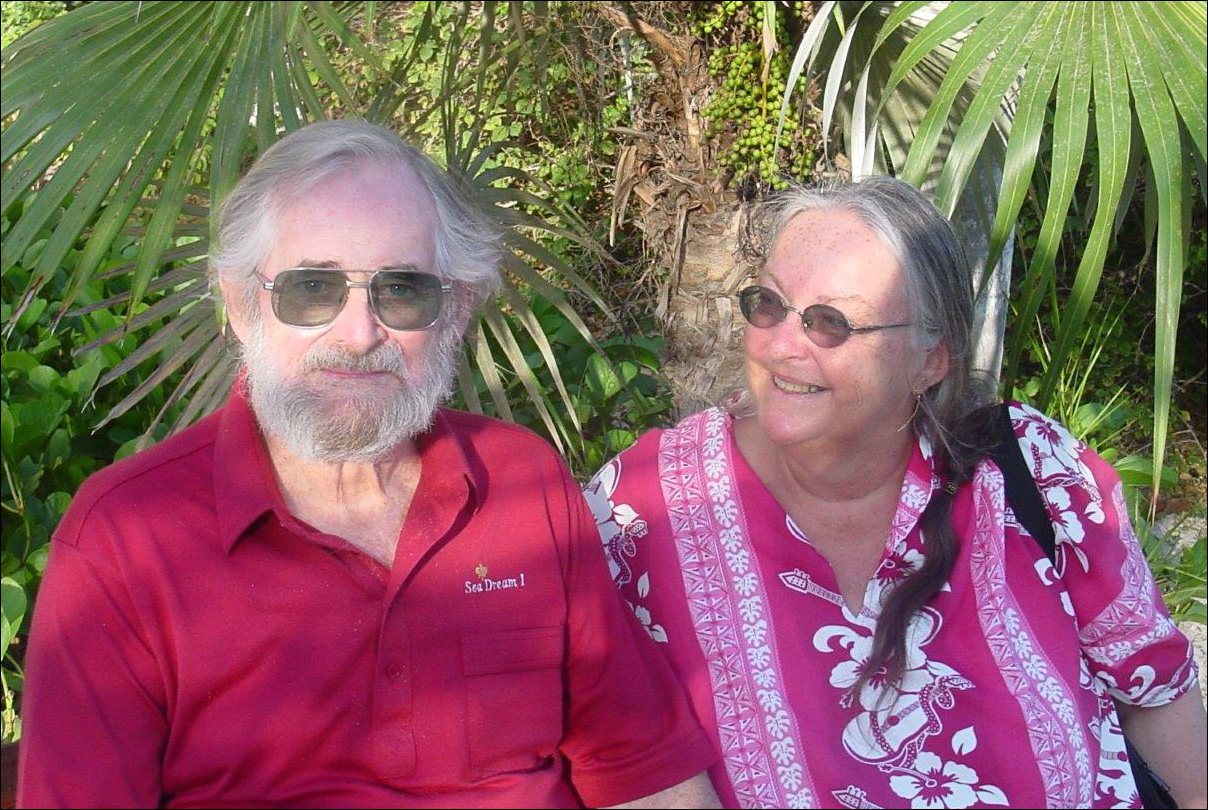

We were sailing our Morgan 41, Sea Dream I, from Grenada to Antigua. The Christmas Winds had arrived early and were in force. We’d had a truly awful night sailing from Carriacou to St. Lucia — black as the inside of an elephant with winds that never dropped below 30 knots, plus hourly squalls of 40 to 45 knots.

In spite of all that, my husband, Vern, and I weren’t expecting what hit us just north of Martinique: a squall with 55-knot winds and gusts to 60. It lasted only ten minutes, but felt like ten hours as we clung grimly to the wheel.

In spite of all that, my husband, Vern, and I weren’t expecting what hit us just north of Martinique: a squall with 55-knot winds and gusts to 60. It lasted only ten minutes, but felt like ten hours as we clung grimly to the wheel.

The main blew out and then, once the winds calmed down to only 40 knots, Vern noticed a line trailing along the lee side of the boat. I was upset to realize that it was all that was left of our Fortress anchor. We had lost 100 feet of chain and 200 feet of rode. A lot of water must have come over the bow during the squall, with enough force to lift the pawl off the windlass gypsy and let the anchor run.

With the main blown, we needed the engine and didn’t want any lines tangling in the prop. Vern said, “Be very, very careful!” as I went out on deck and up forward to haul the line in.

I was sitting on the foredeck with the windlass between my knees and one hand on the windward lifeline — and them suddenly I wasn’t! Sea Dream and I had parted company. It’s a distressing sensation being run over by your home, but somehow I managed to kick out from under the hull before I got aft to the propeller.

Vern brought the boat around immediately and I was expecting to be run down again, but managed to grab the trailing anchor rode, which immediately pulled me underneath the boat again. Even with the engine out of gear and a blown-out main, 40 knots of wind and six- to eight-foot seas push a boat along at a fair clip and I couldn’t hang on without being dragged under. The next time Vern came for me he threw the jibsheet over the side. That was better, as I could let myself trail aft of the boat and not be sucked under the hull.

The next thing I remember was trying to climb aboard using the rudder extension for the wind-vane oar. I still had the figure-eight stop knot of the jibsheet tight in my right fist. Vern was standing at the stern knotting a line to hand to me. I got as far as standing on the rudder with both hands on the rubrail, moved one hand to grip anything that wasn’t slippery with salt and away I went again. Seconds later Vern had the line ready to throw — and couldn’t see me.

By this time it was 0900 hours, which meant we were 12 or 15 miles north of St. Pierre, which we’d left at 0600. Vern put out a “Mayday” on VHF channel 16, which was heard by at least two sailboats and the girls at the reception desk of the Anchorage Hotel in Dominica. But two other sailboats that were close to us heard nothing. (When they saw our sailboat going in circles didn’t they wonder if there was a problem? At least with the seamanship?) The two boats sailed serenely past, without changing course for a closer look.

It occurred to me that I’d be more visible waving a flag, and I tried waving my T-shirt. It’s a knee-length red beach cover-up and, dry, would make an excellent signaling device. Wet, not so great. Try some time waving a soaking wet T-shirt overhead while swimming in six- to eight-foot seas! It’s heavy, for a start.

I stretched it out between my hands and threw it into the air as I reached the top of a wave, but I didn’t have much hope. A successful sighting would have required me being on top of a wave, Sea Dream being on the top of a wave and Vern looking in exactly the right direction, all at the same time. It didn’t work. I decided to put the shirt back on for modesty’s sake.

Vern circled for an hour, searching for me. It didn’t take me long to find out that with the wind pushing it, Sea Dream was drifting off faster than I could follow, so I stopped trying. We’d joked once that if I fell overboard he should just carry on to the next island and I’d swim in, so I headed for Dominica. I’d lost my glasses in the fall overboard but could see Dominica. Martinique was lost in squalls and rain. I turned my back to the wind and swam.

Vern, meanwhile, was having a perfectly awful day. For one thing, it was the first time he’d single-handed in the nearly 12 years since we retired aboard. At least the winds hadn’t piped up to 55 knots again, but with the blown sail down to the reef point and having to stand on the cockpit coaming to reach the reefing lines Vern didn’t have much to hang onto. He was nearly overboard himself more than once. (Which would have been a real disaster as he has negative buoyancy, as do about three percent of all people. Unlike me, he carries no built-in flotation.) At last he controlled the sail and headed north (in Dominica they speak English) to organize a search. But all the way, he was trying to work out how to break the news to my family that I had drowned.

It took Sea Dream until nearly 1700 to get close to Roseau, when three local men in a boat came out almost a mile to welcome Vern to the island and offer help. He certainly needed it! In moments Brian, James and Darryl were aboard. Brian was on the radio to the Coast Guard to report my loss, since Vern doesn’t hear well and couldn’t understand the questions they asked. Darryl was right inside the chain locker reeving the second anchor chain through the primary hawse so the boat could be anchored, and James was on the stern preparing lines to carry ashore to a palm tree.

My day was much easier. I knew I was fine, and could tell Vern was still aboard and coping because the boat was under control.

The funniest things go through your head when you’re swimming alone between islands. Mostly I was furious for making whatever elementary mistake let me fall overboard in the first place. All kinds of thoughts went through my head: “I guess I’ll never get those Christmas cards written after all” and “Don’t start throwing away my business-card collection, Vern, because I’ll be back!” and “I suppose he’ll be spending our life savings on a helicopter search…”

A jellyfish tentacle wrapped around my arm and I picked it off and said, “Not now, I haven’t the time!” right out loud. A dolphin swam by 30 or 40 feet away and that was a thrill, finally to swim with a dolphin, even if it was only for a second or two. A small container ship came past about a quarter of mile away, heading west, then changed course to the north, going around me exactly as if I were a pivot.

Of all possible ways to die, drowning would be my least favorite, so I didn’t. Besides, Vern had his first wife for 32 years and I could scarcely demand equal time if I weren’t around. It was necessary to stay afloat.

I thought of all the things that I’d be leaving unfinished, and shrugged. There were no regrets except for the stack of unanswered letters; some we’d even taken to Canada with us and brought back still unanswered. I was glad I hadn’t skimped on telling family and friends I love them. I was glad I hadn’t been tethered to the boat, as I’d have been battered on the way over the side or dragged under the hull until I drowned. I’d taken on quite enough water just trying to hang on by the broken anchor rode.

Just at noon, I saw a sailboat heading my way and thought, “Can’t be Vern; he doesn’t have a jib out.” Soon the boat was so close that if a wave hadn’t smacked the bow aside I’d have been run over again!

I yelled “Hey, can you see me?” but they already had. Anthony said, “There’s someone in the water!” and Justin had looked around to see who was missing. From there, the rescue was textbook perfect. Anthony never took his eyes off me as Justin managed the jib and brought Enchantress around to circle me. Her dinghy was out on a very long painter and they maneuvered it around so I could grab hold. I told them I was very tired, which was not strictly true, and would need a ladder to get aboard, which was true. I’ve never been able to climb out of the sea into an inflatable dinghy, so I just clung on to theirs until they put a ladder down. Then they towed the dinghy in, threw me a line to knot around my chest and towed me to the foot of the ladder. I was soon aboard and provided with a dry towel that was colour-coordinated to my red T-shirt.

Enchantress had a touchy transmit button on the VHF radio and so used a hand-held unit to tell their companion boat, Natasha, that they’d picked up a hitch-hiker. On Natasha, Federica passed messages on to anyone who would take them — to let Vern know I was fine, to stop him initiating an expensive search, and to get him some help securing the boat in harbour. The message went through to Sudiki, a Gulfstar 50 sistership to Enchantress. (While Federica was on the radio, a female French voice broke in to tell her to get off channel 16 as it is for emergency and rescue! When I met James and “Freddy” later, I asked her what she had said in reply and got a flood of Italian. Though I didn’t understand, I suspect there is a Frenchwoman around with a blistered ear.)

Enchantress and Natasha were headed for Fort-de-France. I badly wanted to go to Dominica and nearly asked to be thrown back in, but common sense prevailed. As soon as we arrived, Justin took me ashore to ask about ferry times. No luck, as the depot was closed tight. Next it was back to the dock nearest the anchorage. He went off to find a policeman to report me to, and I went to Customs on the off chance that it might be open.

A lovely young bride was posing for photographs in the garden as I trudged through, barefoot, blowsy, tousled, salty and myopic — with luck I walked behind all the family cameras. Customs was shut, and I spent a frustrating quarter-hour with the French phone system, discovering that it’s impossible to find an operator. The only toll-free number to answer yielded a fireman who listened to my tale of woe politely in spite of my terrible French, and assured me he knew of no way to call an operator either.

Back I went through the wedding party, now photographing bride and groom with their youngest attendants. Soon Justin and a pair of police officers arrived; my final view of the bride was as she picked her way to her car, blocked in by the police vehicles, and past my disreputable-looking self being grilled by the gendarmes. The police left us with names and phone numbers to show Customs we’d spoken to them and assured us that someone would call Dominica’s Coast Guard and abort any search plans.

My rescuers fed me, put me to bed, and lent me the fare to Dominica. The next morning I got the sixth-last seat on a 350-passenger ferry.

Meanwhile, Vern was still having adventures.

Just at dark, he finally learned I’d been rescued, when Chris and Duff of Sudiki came by and told him the news. Later they collected him, fed him, let him talk and wind down, put a call through to Enchantress via cell phone, Crosma and VHF radio, and generally made it possible for Vern to sleep that night.

Next morning early, Brian and James, who had welcomed Sea Dream to Dominica, were back to check up on Vern and help him move the boat to a mooring since it was gradually dragging ashore, when the Dominican Coast Guard came alongside with three officers aboard. One stayed in the bow with a 12-gauge riot gun pointing at Vern, one managed their boat with an automatic rifle across its seat, and the third came aboard Sea Dream and got Vern’s attention by taking him firmly by the arm.

“You are under arrest,” he said. “Pack a bag, lock the boat. You may be away for some time.” Vern faced three charges, in this order of importance: allowing Dominican nationals aboard before clearing Customs, not clearing Customs immediately upon arrival, and doing away with his wife.

Once Vern was in the police boat there was no further chat. He was taken to the head office of the Coast Guard, which is also the police force, and helped ashore since the landing is difficult. It took some time to produce a statement. Partway through, the atmosphere became much more civil.

Afterwards, one officer kindly pointed out a bakery where Vern could buy a much-belated breakfast. Then Vern was bundled back into the boat and taken to the ferry dock, where he cleared in through Customs and Immigration. Without pausing to think, he put my name on the crew list. The Immigration officer crossed it off with a scowl, saying, “We’ll clear her in if she arrives.” IF!

Vern was still waiting on the dock when the ferry decanted me at 4 o’clock that afternoon — and I was very pleased to see him.

We’ve proved it again: it ain’t over till the fat lady SINKS!

This article first appeared in the April 1999 issue of Caribbean Compass.

About Ruth Chesman

Canadians Ruth Chesman and her late husband, Vern, cruised the Lesser Antilles island chain in the Caribbean for many years aboard their Morgan 41, Sea Dream I.

Back home in Canada, the Chesmans were active members of the Fanshawe Yacht Club of London, Ontario. Ruth was always able to see — and communicate — the funny side of sailing, even in a potentially fatal situation. Her stories have appeared in Cruising World and Scuttlebutt, as well as in Caribbean Compass.

Cruising Life:The Best Stories from Caribbean Compass

Outstanding stories by cruisers, of cruisers and for cruisers!Compiled by Sally Erdle and Rona Beame JUST LAUNCHED: a new collection of outstanding cruising tales from the Caribbean — from the dramatic true story of a woman falling overboard to hurricane survival to a hilarious black-market expedition to a hair-raising journey on a local bus. These stories span a vibrant region, from St. Croix to Cartagena and from Barbuda to Guatemala. Cruising cooks share gourmet galley secrets and poets offer rocking rhymes for island times. Sailors spin yarns about coves where few have dropped the hook, as well as providing offbeat looks at islands everyone “knows”. Cruising Life The 49 stories in Cruising Life were written by cruisers, both professional writers and amateurs, for Caribbean Compass, the monthly magazine that boaters say is a “must read” for anyone sailing in, or planning to visit the Caribbean. Editor Sally Erdle says, “Weʼre excited to now offer this lively and far-ranging selection of original Caribbean cruising writing to readers around the world. Old salts will grin with recognition, and those just casting off will be inspired!” ISBN 978-976-95602-0-8 You can read the Caribbean Compass FREE online every month. |

I’d love to take credit for involvement with the Fanshawe Yacht Club, but that is Paul Chesman’s baby. He held the post of commodore for three years, breaking the one- year tradition definitively. -ruth-

Great story! Thanks for sharing.