This article was first published in the Ocean Cruising Club publication Flying Fish.

|

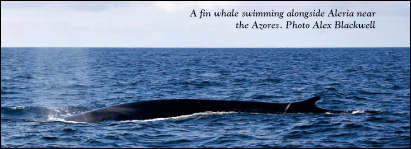

| A fin whale preparing to dive beneath ALERIA’s bow. Photo Alex Blackwell. |

Most sailors setting off on a passage dream of encountering wildlife at sea.

Yet ask blue water sailors about their biggest fears, and near the top of the list is likely to be ‘striking a whale’. It’s one of the events most likely to be catastrophic at sea. Today, we can usually avoid really bad weather, but can we avoid a sleeping whale at night?

And what is the likelihood of a chance encounter with a whale? It may not be as rare (or as common) as one might think, depending on location. The likelihood appears to be increasing as protected whale species increase in numbers, and like many cruisers Alex and I have had a few very happy encounters.

Fortunately, several lessons can be applied to reduce the risk and enhance the experience.

Magic at sea – the friendly encounter

First encounter with whales

|

| Whale spy hopping on Stellwagon Bank. |

Our first encounter with whales came while crossing Stellwagen Bank, a vast marine sanctuary off Cape Cod. We came upon a pod of northern right whales (Eubalaena glacialis), which started us off with a magical experience that would be difficult to top. We first sighted a mother and calf feeding near tour boats – she was ignoring the humans intruding on her brunch.

About an hour later we noted a rock where there should have been deep water.

|

After frantically checking the charts and keeping a close eye through binoculars, we realised it was a whale with callosities, spy hopping and being groomed by a flock of birds. Then the whale rolled and dived to show off his fluke.

Soon afterwards a second whale appeared, much closer, then two more, and five more, until we were surrounded by scores of these leviathans.

As they came closer to get a better look at us with those all-knowing eyes, our first thoughts drifted to the infamous line from Jaws, “we’re gonna need a bigger boat”. They were about the same length as Aleria.

As soon as we realised they were just curious and respectful we ghosted along beside them as we checked each other out. We were under full sail in light winds with no engines running, and worried about them surfacing beneath us after their dives. We kept a close watch, steered cautiously away from any ahead of us, and avoided coming between mothers and their calves.

Whereas the experience was initially silent, suddenly the air filled with whale song. Not just one but a cacophony of voices, which seemed to be amplified by Aleria’s hull acting like a stethoscope. There were long wails, short burps, moans, groans, and high pitched squeals of varied duration and emphasis. We were taken aback, perplexed. We looked at each other to make sure we were both hearing this. It sounded surreal. Then, we succumbed to the sheer joy of it. We sang back, jumping up and down, cheering and clapping like children. I don’t recall ever having had such a joyous experience in my life. We were speaking whale! All fear was gone, replaced with sheer wonder. It seemed to go on forever.

Then, suddenly, they were gone. The whale song receded and the whales disappeared from view. We mourned their passing but felt blessed to have met them. Alex described the experience as ‘prehistoric, otherworldly’. We had been so dumbfounded that we forgot to take pictures. We have only a few that Alex took as he sighted that first ‘rock’.

Occasional glimpses

As we left Nova Scotia to cross the Atlantic to Ireland, we were followed out of St Margaret’s Bay by a lone killer whale (Orcinus orca). She swam along peacefully and we wondered if her reputation was deserved. We didn’t see any more whales all the way to Ireland, but we sailed through thick fog followed by six gales. We know now that whales are sighted more often on calm, clear days – if the surface of the sea is smooth, you’ll spot an unusual disturbance more readily.

We were next rewarded with a visit by a pod of pilot whales (Globicephala macrorhynchus) while in transit from Tenerife to La Gomera in the Canary Islands. They are known to be resident there, so we kept a close watch. Not much bigger than dolphins but black in colour, the pilot whales swam gently along in company for some time.

|

| A pilot whale off La Gomera in the Canary IslandsPhoto Martina Nolte / Lizenz Creative Commons CC-by-sa-3.0 de |

During six months of cruising the Caribbean, where whales come to calve, we saw only one, breaching off the west coast of Antigua. From the shape and acrobatics it appeared to be a humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae). In certain islands, the Grenadines for example, fishermen are permitted to take their annual quota of whale meat in the traditional way, and as we passed St Vincent we saw a boat with a bow-mounted harpoon coming in with a cetacean strapped to the side of the hull.

Whales galore

|

Crossing the Atlantic from the Caribbean to the Azores, we encountered very light wind conditions. In fact, the Azores high overtook us until we were smack in the middle. It was on this leg that we learned the value of a flat sea for whale sightings and learned just how many of these creatures are en route through the area at any given time. No wonder the Azores were so prominent on the whaling scene. Plentiful food, good weather – what’s not to like?

We had numerous sightings on one day – sperm whales (Physeter catodon) and fin whales (Balaenoptera physalus), mothers with calves, juveniles and elderly, in the distance and REALLY close by. In fact, one pod swam along in our bow wave like dolphins, except they were 60ft long fin whales. They dove underneath and we wondered where they’d come back up. They blew air which carried the scent of bountiful fisheries right beside us and stared at us with those penetrating gazes. It happened to be my birthday – one I will never forget!

In all these encounters, we have never truly felt threatened – concerned about proximity, but not threatened. We rarely use the engine even in very light air, and we always keep a close watch. We are respectful of the distance between us. We are respectful of their environment. We are respectful of their intelligence and their place on this oceanic earth. I think they knew all that.

Collisions between ships and whales

Struck by a whale off Grand Banks

The first time I heard about a sailing boat ‘encountering’ a whale mid-ocean was when a yacht, the 49ft sloop Peningo, collided with a whale about 700 miles from the Azores while en route from the US to the America’s Cup Jubilee in England in 2001.

The skipper wrote about their ordeal afterwards, providing insight into the experience1. Although the story is entitled Struck by a Whale, from his description of the encounter it is more likely that it was the vessel that struck the whale. The whale was severely injured and the yacht was rendered helpless with serious rudder damage. Luckily for those aboard, the yacht remained afloat with no major water intrusion until a rescue ship arrived to tow them back to Newfoundland.

The whale probably didn’t do so well.

The sinking of the Essex

|

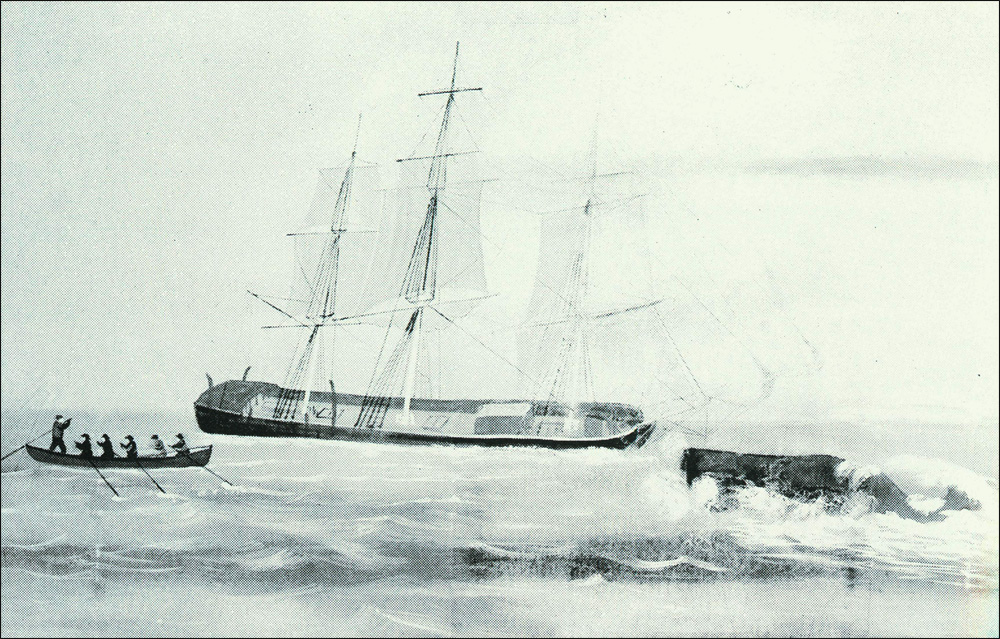

| This illustration from the Russel Purrington Panorama – a series of paintings intended to describe the workings of the whale fishery – shows the attack of the whale on the Essex |

A most famous encounter is that of the Nantucket whaling ship Essex, which was sunk by a sperm whale in the South Pacific2 in 1820. Herman Melville’s novel Moby Dick

is based on this true story, told by the few crew who survived. The whale struck the Essex with its head just behind the bow while the light boats were out hunting.

‘The ship brought up as suddenly and violently as if she had struck a rock,’ recalled Owen Chase, the first mate. The whale had smashed through the bulkhead and water was streaming in. Chase set the crew to work on the pumps and signalled the other boats to return immediately.

The whale, meanwhile, was apparently badly injured and was leaping and twisting in convulsions some distance away. Then suddenly the animal raced toward the ship again, its head high above the water like a battering ram.

It stove in the port side of the ship and the Essex sank, leaving the crew thousands of miles from land in three light boats. (See Nathaniel Philbrick: In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex Penguin, 2001.)

In a scientific paper on whale behaviour by Carrier published in 2002, the authors note, ‘Head-butting during aggressive behaviour is common and widespread among cetaceans, suggesting that it may be a basal behaviour for the group. Although data is not available for most species, head-butting has been observed in species in each of the four major cetacean lineages’. They put forth a hypothesis that the spermaceti organ has evolved in whales as a weapon used in male-to-male aggression and was used as a battering ram capable of sinking the Essex. (See Carrier, DR et al: The face that sank the Essex: potential function of the spermaceti organ in aggression. J Exp Biol 205: 1755-1763, 2002.)

Even without this, the sperm whale is the largest-toothed animal alive today with some growing to more than 60ft in length and weighing 50 tons.

|

| A mother sperm whale and her calf dive together near the Azores. Photo: Daria Blackwell |

Whale attack! Yachts colliding with whales

During a passage from the Canaries to the Caribbean we heard one of the boats in our SSB net report an attack by a whale.

She was a vessel in the 35ft range, heading back to Boston from Europe with two people aboard. While under sail in light wind they sighted several whales, one of which turned towards their boat and rammed it head on. It circled, and came back at them repeatedly. They were terrified that the whale was going to keep battering until they were holed and sunk, then suddenly it swam away. They had the presence of mind to take photos and were able to identify it as a false killer whale (Pseudorca crassidens). The net controller asked what colour their hull was, as a crew member suggested that whales tend to attack boats with red bottoms. Interestingly, they had just had their bottom repainted – and the colour they had chosen was red. Aleria’s bottom is green and her hull is white.

There are multiple reports of yachts colliding with whales, including two in the 1970s when British yachts were lost.

• Maurice and Maralyn Bailey were on their way from Panama to the Galapagos Islands when, at dawn on 4 March 1973, their 31ft Auralyn was struck by a whale and holed. The Baileys survived for 117 days and drifted 1500 miles on an inflatable liferaft before being rescued. They wrote an account of their ordeal entitled 117 Days Adrift

(Staying Alive! in the US).

• Dougal Robertson left England in 1971 aboard Lucette, a 43ft wooden schooner, with his wife and four children. On 15 June 1972 Lucette was holed by a pod of killer whales and sank approximately 200 miles west of the Galapagos Islands. The six people on board took to an inflatable liferaft and a solid hull dinghy, which they used as a tow-boat with a jury-rigged sail. They were rescued after 38 days by a fishing trawler.

Robertson wrote two books, Survive the Savage Seaand Sea Survival: A Manual.

• More recently there’s the 1989 account of a pod of pilot whales sinking the yacht Siboney, after which owners Bill and Simone Butler awaited rescue in a liferaft. He documented their story in the book, 66 Days Adrift: A True Story of Disaster and Survival on the Open Sea.

• In October 2011 Yachting Monthly reported on a boat which had been attacked by a whale mid-ocean in the mid 1990s. The animal made three glancing blows before swimming away, and scientists whom the author spoke to afterwards suggested that she must have had a calf and was chasing them off. They did not report the colour of their bottom paint, but noted that sections of paint had been scraped clean in the collision. The vessel, an Oyster Lightwave, did not suffer any significant damage.

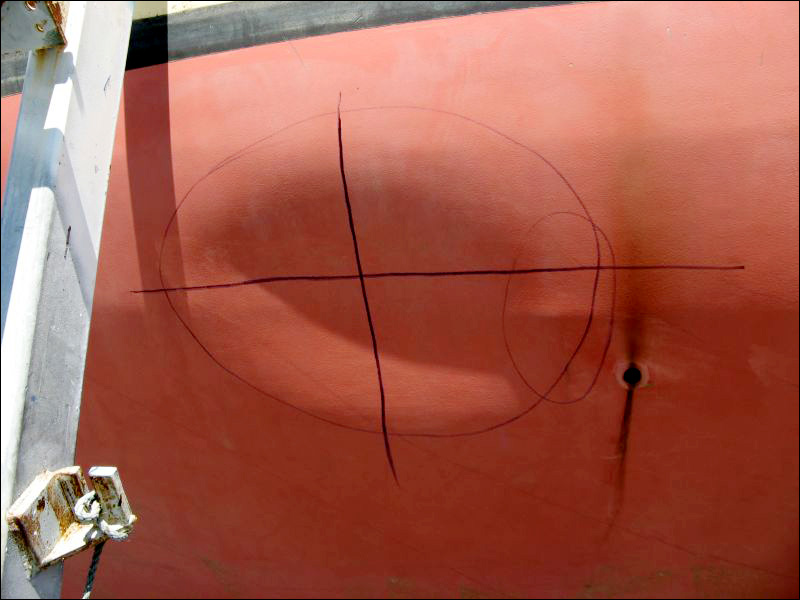

|

• Anecdotal reports on blogs include one by Paul J who reported being attacked by what may have been a sperm whale about 150 miles off the Great Barrier Reef. He posted a photo (right) on ybw.com of the bottom of his steel boat dented by the whale’s head – the bottom of his boat was painted red.

In the same thread, two other cruisers noted encounters with pilot whales around their redbottomed boats, but no attacks.

Can whales see colour?

It has long been advised not to paint a boat’s bottom white because it looks like the belly of a killer whale. Other people advise not to paint it black, grey or blue because it might appear to be a competing whale or a predator. Then the red question came about.

Yet scientists have long professed that whales cannot see colour as they do not have the short wavelength cones in their eyes. That to me is short sighted (excuse the pun) as it assumes the human way is the only way to see colour. A study published in 2002 by Griebel suggests that cetaceans do indeed discern colour, but in a different way than we do (See Griebel, U, Color vision in marine mammals. A review. Bright, M,Dworschak, PC, and Stachowitsch, M (Eds.) 2002: The Vienna School of Marine Biology: A Tribute to Jörg Ott. Facultas Universitätsverlag, Wien: 73-87.)

So it is possible that colour does make a difference to whales – we just don’t know for sure.

Speed is a factor

One certain trend is that more collisions are being recorded as boats get faster (especially racing boats). A British sailing journalist’s blog looked back at some of the better-known collisions with whales, and we have now added to the list. There are four reports of collisions during the OSTAR (one in 1964, two in 1988 and one in 1996) the latter including one with Ellen MacArthur’s Kingfisher in which the whale was killed and found wrapped around the vessel’s keel. David Selling’s Hyccup sank as a result of a collision in 1988.

There were two reports during Whitbread Round the World Races, in 1989 and 1998; of the second, Knut Frostad said, ‘It was like being in a car crash’. Delta Lloyd and Ericsson 3 both hit whales during the 2008/09 Volvo Ocean Race, with minor damage.

There were four other reports during races between 2001 and 2005 in which boats were damaged, with rudders being particularly vulnerable.

That’s a total of twelve high-profile collisions reported since the 1960s, but only one vessel (Hyccup) was catastrophically damaged.

And in the 2011/12 Volvo Ocean Race, Camper’s helmsman Roberto Bermudez managed to avoid collision with a whale on Leg 7 from Miami to Lisbon – all caught on amazing video footage

YouTube video: CAMPER Avoids Whale Collision – Volvo Ocean Race 2011-12

Next:

Part 2 of this article is here.

About Daria Blackwell

Daria Blackwell is a USCG licensed Captain. She and her husband Alex, and cruising kitty Onyx, have crossed the Atlantic three times in three years aboard their Bowman 57 ketch Aleria, spending years cruising the Caribbean and Atlantic islands as well as the American and European coasts. They are now in Ireland planning their next adventure.

Daria is a proud member of the Ocean Cruising Club Committee, Seven Seas Cruising Association (cruising station for Ireland), American Yacht Club and Mayo Sailing Club.

Daria is a proud member of the Ocean Cruising Club Committee, Seven Seas Cruising Association (cruising station for Ireland), American Yacht Club and Mayo Sailing Club.

The Blackwells are co-authors of Happy Hooking – The Art of Anchoringwhich has received excellent reviews in the sailing press. They periodically conduct their Happy Hooking webinar for Seven Seas University.

Their website is www.CoastalBoating.net, “the boaters’ resource for places to go and things to know”.

Further readings

- Dod A Fraser: Struck by a whale off Grand Banks

- Wikipedia: Essex (whaleship)

- Herman Melville: Moby Dick

- Nathaniel Philbrick: In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex

Penguin, 2001

- Carrier, DR et al: The face that sank the Essex: potential function of the spermaceti organ in aggression. J Exp Biol 205: 1755-1763, 2002

- Maurice and Maralyn Bailey: 117 Days Adrift

- Dougal Robertson: Survive the Savage Sea

& Sea Survival: A Manual

- Bill Butler: 66 Days Adrift: A True Story of Disaster and Survival on the Open Sea

- Yachting Monthly, October 2011: Whale attack! When a 6-ton boat met 12 tonnes of blubber

- ybw. com forum thread: Pilot whale attacks

- Griebel, U, Color vision in marine mammals. A review.Bright, M,Dworschak, PC, and Stachowitsch, M (Eds.) 2002: The Vienna School of Marine Biology: A Tribute to Jörg Ott. Facultas Universitätsverlag, Wien: 73-87.

- YachtingMonthly.com: Whale collisions a perennial risk, by Elaine Bunting

Also on this website

- Chance encounters between ships and whales – Part 2

- All posts about Nature

- More posts by Daria Blackwell:

- Dancing in the Harbour

- What I like best about cruising? Passages and anchorages: a world of your own

Interesting article. My first encounter with a whale was on a fishing boat off the BC coast in Canada. A killer whale named Luna was visiting and also damaging boat rudders in the area. The whale was said to Bethesda reincarnate grandfather of the local First Nations people. Government wanted to try to reunite Luna with her pod. First Nations said no. They tried to manage her boat contact but eventually she was killed. She visited our boat twice within a week in two very distant locations. Seeing her up close was magnificent. We even overlooked the fact she broke motor mount for our kicker.

Hi Karen,

Interesting note, thanks for that. We saw a lone killer whale in Nova Scotia in 2008.I wonder if it was Luna.

What a wonderful experience! I have been swimming and heard the whales off the coast of Hawaii but not the joy and wonder that you described as whales surrounded your boat. That must’ve been magical! We did see a pod of Orca whales in New Zealand and foolishly chased them in our dinghy to photograph them…weeks later, we were horrified as we watched a BBC program about how killer whales drown seals by flopping on top of them (and there we were in our gray dinghy – what were we thinking?!). Thanks for sharing your knowledge and story.

Lovely story Kelly. People oftem forget these magnificent creatures are “wild”!

Another report has just come to light. This one in the ARC Europe off Bermuda last month.

http://bernews.com/2012/05/yacht-abandoned-after-it-strikes-whale/#comment-720323

Interesting read. We were toned by a humpback inside the Great Barrier Reef last year. The conditions: it was dead flat, no wind and we were motoring at 5 knots with one engine on (catamaran), about 11 am good visibility, sunny bright day. I’ve always been old whales will hear your engine and stay away but not the case.

Either it hit us or was just under the water going across us as it hit one hull amidships enough to lift one hull about a meter out of the water. It then hit the other keel and popped out the other side.

We couldn’t see any damage to whale but hubby was more concerned with our hull as it was like hitting a big rubber bus With no apparent damage we went our respective ways. I used to say “oh I hope we see a whale” ill never say that again. I’m happy to see them on TV.

Thanks for sharing Rozzie. I’m glad there weren’t any injuries!