|

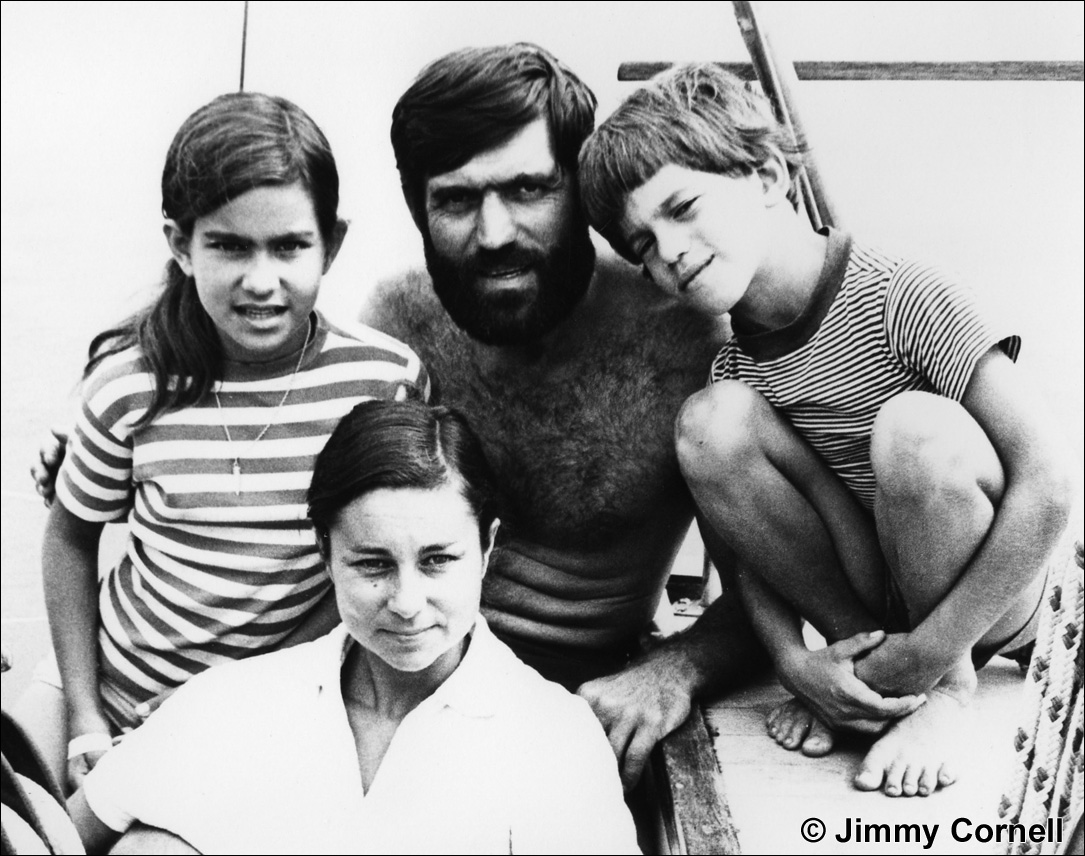

In 1975 my family left our home port in London, England, and set off cruising. I was seven at the time, my brother Ivan five, and apart from returning home that first winter, we didn’t set foot in England for another six years, when we returned, having completed a circumnavigation.

There’s no doubt that the world has changed a lot since 1975, and yet, when I read the stories of other cruising families posted on this website, I am struck by how similar they are to the experiences I had with my family.

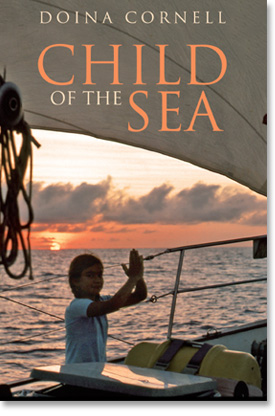

I have often reflected on my sailing childhood, and how it has made me what I am today. At the start of 2010 I decided it was time to put it into words, and I began to write; in the spring of 2011 my book Child of the Sea was finished.

I wanted to portray a sailing childhood as accurately as possible, and I wrote with an audience of children in mind. I drew on my own memories, my diaries and stories, and

once I had written the first draft, my mother and I discovered a cache of weekly letters she had written to my grandmother that helped fill in the gaps. I wanted to portray a sailing childhood as accurately as possible, and I wrote with an audience of children in mind. I drew on my own memories, my diaries and stories, and

once I had written the first draft, my mother and I discovered a cache of weekly letters she had written to my grandmother that helped fill in the gaps.

Plus my father had taken hundreds of photos which I spent hours poring over, reliving the experiences and imagining myself back into the skin of a young girl.

Naturally, my parents figure very prominently as characters in the book. It was their determination which set us off sailing. Mum and Dad to me, you may know them as Gwenda and Jimmy Cornell, well known to cruising sailors around the world. Of course it wasn’t like that when we started – Dad was as much a novice as anyone.

Excerpt from Child of the Sea

Maiden Voyage

The waves were bigger now and spray was hurling itself onto the decks. At least the cockpit was protected by the wheelhouse. I glanced up at Mum sitting at the steering wheel. She gave me a weak smile. She looked pale and ill too.

I staggered from handhold to handhold to the companionway, where the steps led down to the main cabin. My hands trembled but I tried to hold firmly on as I put my foot on the first step.

‘Doina, turn around!’ I was being yelled at again. ‘Have you forgotten how to go down the steps?’

‘Mmm,’ I said, trying to move my mouth as little as possible. Turn around and go down backwards. Hold on. How could I remember all these rules, when I was feeling so sick?

Down below the boat’s movement was even worse.

‘There’s nowhere to lie down,’ I moaned. If only this banging up and down would stop. Ivan sat on the floor, clutching the washing-up bowl.

‘Lie on the floor.’ Dad came down the companionway. He didn’t feel even the slightest tinge of seasickness. ‘The movement isn’t so bad there.’ He spread out some cushions and swapped Ivan’s full bowl for a clean bucket.

We squeezed together like sardines on the floor.

‘Doina,’ Ivan whispered.

‘What?’ I said crossly.

‘Will it get better? I feel horrible.’

‘I don’t know. I feel horrible too.’ |

Eventually we got our sea legs, and I began to love our onboard life.

People talk a lot these days about what makes a good childhood. I have to say, a sailing childhood is about as perfect as it gets.

Excerpt from Child of the Sea Getting Used To Our New Life

|

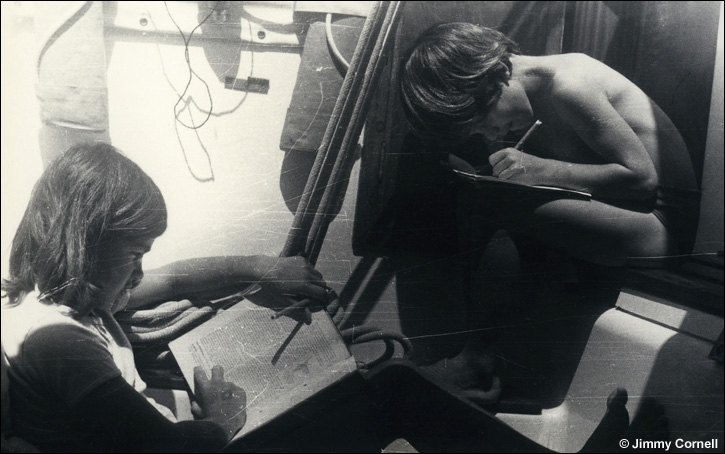

| School work in the cockpit |

We didn’t stay long in Gibraltar. Even though Dad was a UK resident they only gave him a 2 day visa. He’d had to give up his citizenship when he left Romania so he now was a stateless person and had to get visas for every country we visited, which were stuck into his stateless passport, which wasn’t really a passport at all, but a big folded up piece of paper.

Also, it didn’t stop raining, and the Rock had clouds permanently wrapped around its peak.

The sun came out as soon as we sailed away.

‘Let’s play,’ I said to Ivan. We grabbed an armful of toy animals each and took them into the main cabin.

Mum looked through the companionway.

‘Good, I see you’ve got your sea legs. You can start on some schoolwork.’

‘No!’ we protested, but we had to do it. There were plenty of English and Maths books, given to us by our London school before we left. Mum sat with Ivan, listening to him read. I started copying out a list of spellings.

‘This is stupid,’ I complained. ‘The sea makes my writing all wobbly.’

‘Children come quickly!’ Dad shouted.

We dumped our books and raced into the cockpit. Dolphins were breaking the surface of the sea next to the boat, their blue-grey skins shiny from the water. ‘Quick, go up to the bow.’

‘What about harnesses?’ Mum asked.

‘Never mind that!’

I peered over the pulpit and there they were, a group of them, speeding fast through the water. They swam back and forth, right in front of the bow.

‘They’re riding the bow wave,’ said Mum.

‘Why?’

‘They like the feel of it on their skins, I guess.’

‘Maybe it tickles.’

Suddenly one big dolphin jumped very high out of the water. It was a wonderful, exciting sight. I thought my eyes would pop out of my head.

|

| Watching dolphins from the bow, Mediterranean |

|

|

|

Our favourite place,

up the mizzen spreaders |

|

Enjoying a bath in the dinghy

after a downpour in Panama |

|

Excerpt from Child of the Sea French Polynesian Anchorage

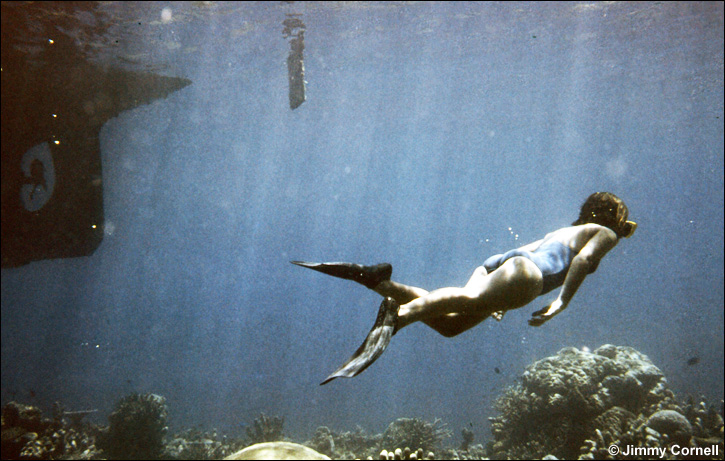

Aventura anchored near the beach. The turquoise water was so inviting that Ivan and I had our masks and flippers out and were ready to go when the anchor had barely touched the ground.

I let my grip on the boat go and dove below the surface, without a splash. In every direction the plains of sand stretched off into the blue misty distance. There was the underside of Aventura, the deep, strong keel, painted with blue anti-fouling paint, but shaggy with months of sea-growth: long strands of green weeds and hard white barnacles. From the bow the thin strand of the anchor chain fell steeply down to the sand in a heavy curve and snaked off along the sea bed to where the anchor was safely dug in. I hauled myself hand over hand down the chain to reach the bottom faster. Then I turned and looked up at the waves. They looked funny upside down, or was it inside out, like a moving silver sky.

I spent hours in the water with my mask and snorkel. The world I knew beneath the surface of the sea was where I felt at home. |

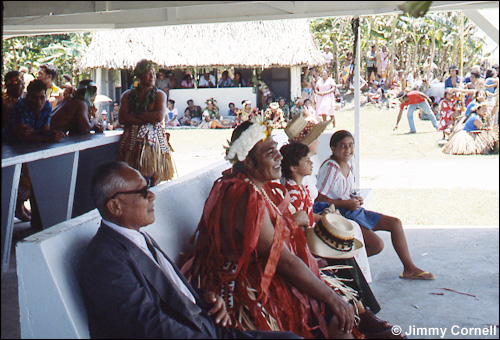

Our only source of income was from my father’s regular radio programme for the BBC, and any articles he and my mother wrote. The search for good stories sent us frequently off the beaten track, to places few if any yachts ever visited. Such as when we headed north from Fiji to witness a new nation being born, as Tuvalu gained its independence from the British empire...

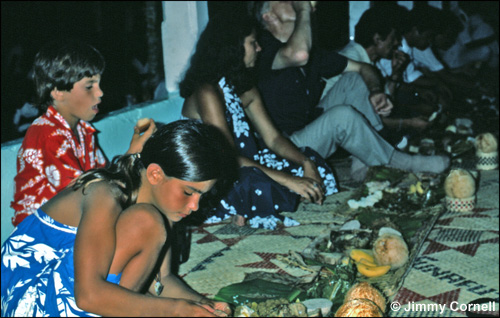

Excerpt from Child of the Sea Tuvalu Feast

|

| With Tuvalu's Prime Minister Toalipi Lauti awaiting the arrival of Princess Margaret |

| |

|

| Tuvaluan feast |

Crowds of people had gathered at the airstrip, dancing girls and singers. Dad was busy with his new cameras. The Chief Minister invited Ivan and I to sit down next to him, in the shade out of the blistering sun. He was a broad-faced smiling man. I looked curiously at him, not having seen a real politician up close before. He was dressed in a skirt of plain dried pandanus, overlaid with pandanus strips coloured and decorated with patterns specific to his clan. A garland of flowers was on his head and his feet were bare. I guess he didn’t look much like a typical politician.

The Princess, slim and dark, stepped off the plane to be greeted by the dignitaries. A girl put flowers around her neck and gave her a fan and she walked down the main street, that was now carpeted with pandanus mats, in the shade of a large umbrella held by another girl, with the Chief Minister by her side.

There was a big feast in the maneapa, the open-sided meeting house, its floor laid with finely-woven mats, the pillars decorated with palm fronds and flowers. Everyone had to take off their shoes and sit cross-legged, which was the traditional style. That was no problem for the VIPs who had come from other Pacific countries, but Mum whispered to me some of the Europeans were ‘creaking a bit’ when they sat down.

When I say feast I really mean it. Long lines of banana leaves had been laid out, laden with piles and piles of food. Roast suckling pig, lobsters in their red shiny shells, baked fish, starchy root vegetables like taro and pulaka, crispy slices of fried breadfruit, leafy greens in coconut milk, rice, potatoes and sweet ripe yellow bananas. There were green drinking coconuts that stood upright in little pandanus baskets. It was a fine feeling for us to be included in the celebrations, on the VIP list and sitting next to politicians and diplomats. |

|

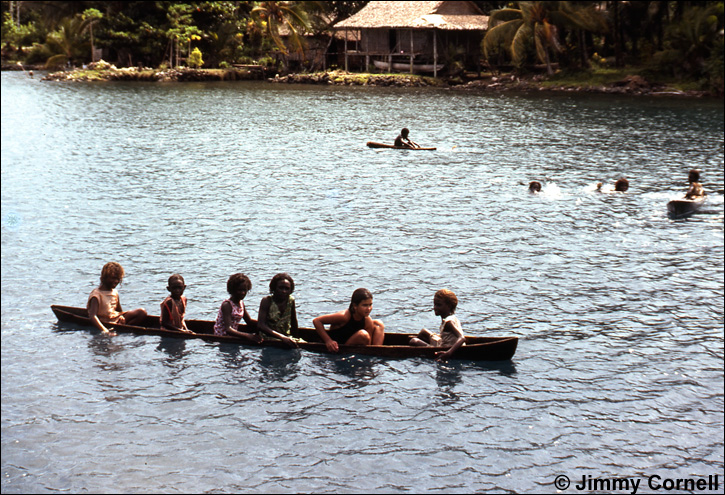

| Ivan, Mum and me in a Trobriand village (Trobriand Islands off the coast of New Guinea) |

In order for Child of the Sea to truly reflect my experiences, I could not shy away from writing about the flaws in the perfection. The first part of our voyage was sweet and easy but when, halfway round the world, I hit puberty aged 12, things got more complicated. We were travelling in parts of the world where pubescent girls are regarded quite differently than in the west, attracting the attention of men and boys. It was a confusing, awkward time for me, which I’ve tried to explore in my book.

My parents had started out with no plans to ever stop cruising; but after three years in the Pacific the decision was made to head back to England so Ivan and I could go to school. My mother had trained as a primary school teacher in order to school us, but it was getting harder for her to teach us. There were still lots of happy experiences, but for the last two years of the voyage my diary was full of regular complaints about not having my own room, or friends that I could keep for more than a few days and one port stopover.

Even so, settling back to life on land was hard. Ivan and I had been to school in all sorts of places, made friends with children from all races in all parts of the world. The first time we weren’t accepted, was when we got back to England.

|

|

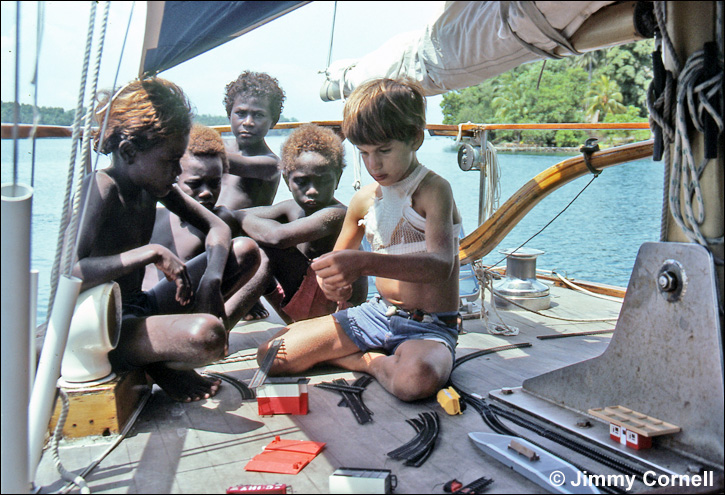

|

Playing with local children in Ugeli,

the Solomon Islands |

|

Ivan sets up his train set on the aft deck,

Solomon Islands |

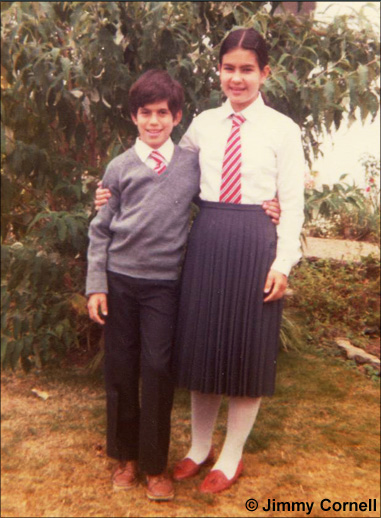

Excerpt from Child of the Sea First day at school

|

| Ivan and I pose proudly in our new school uniforms, England 1981 |

‘Good day at school?’ Mum asked when I came home.

‘Fine,’ I said. I didn’t mention being called a Paki.

‘What about you?’ she asked Ivan.

‘Ok,’ he shrugged. ‘They asked me what football team I supported.’

‘What did you say?’

‘Well, nothing. I don’t know any.’

When Dad arrived that weekend, Ivan had to repeat this story. They thought it amusing. I knew he had found it humiliating. And neither of us said a word to tell them the truth.

That first night as I lay in bed, a great dread settled on me for the next day. I didn’t cry. This is just how it is, I told myself, I can’t do anything about it. |

Years later, I have often talked to my parents about whether we could have done things differently. I am not sure if there is an easy answer. Child of the Sea has a happy ending, at least...

Excerpt from Child of the Sea 10 Years Later, sailing with my grown-up brother

Near to Land’s End everything that could go wrong did – the strong wind was against us, and the tide too. The engine kept coughing and stopping because of dirty fuel. The cockpit was quite open to the waves and the sea hurled itself against the little boat and crashed over me. I’d been steering by hand for hours and my aching hand could barely hold the tiller. Despite my waterproof layers, I thought to myself ‘I’ve never felt this cold before in my whole life. In all the seven years of sailing on Aventura, I never felt this uncomfortable, never.’

But – I looked ahead to the wild dark cliffs of Land’s End, and I realised – it was beautiful. For the first time, I was happy to see Cornwall again. |

|

| With Ivan in Antarctica |

About Doina Cornell

|

| Doina and her own family in Wales, summer 2011 |

| |

|

For many years Doina worked with her father Jimmy Cornell, helping him research his books and working on some of the sailing rallies he’s organised like the ARC. In 2000 she helped him set up noonsite.com which she then managed until 2008.

After moving between London and Prague, now she lives with her husband Julius and children Nera (12) and Dan (9) in a village in Gloucestershire, in a lovely part of the UK countryside.

Doina has loved writing ever since she started writing poems aged 12 in the middle of the Solomon Islands. In 1998 her short story Does the sun rise over Dagenham? won the London Arts Board short story competition, and today it remains a set text on university courses in Europe and the UK.

In 2008 Doina gave up noonsite and trained as a primary school teacher and at present she teaches French in several local schools. Child of the Sea is her first book for children.

|

|

| |